Microplastic quantification refers to the diverse set of techniques used to measure various characteristics of the plastics in a given matrix. Because “microplastics” span a huge range of sizes, shapes, and chemical compositions, no single instrument can fully characterize them. Instead, researchers combine image-based methods (which can directly observe particles), thermal methods (which measure polymer mass by breaking plastics down chemically), and emerging nanoplastic detection tools for sub-micron particles.

The most basic image detection method is stereomicroscopy, which involves taking 2 images from slightly different angles with a “stereomicroscope” to get 3-D information about particles. This can be paired with an image classifier to detect particles greater than .1mm (100 microns). Smaller or transparent particles are difficult to characterize with this technique. Optical microscopy can be improved in some cases by using fluorescent dyes, for example Nile Red. This is a dye that binds to hydrophobic (water-repelling) materials, including most common plastics. When a sample is stained and illuminated with the right light, any stained particles fluoresce brightly while the background stays relatively dark. A fluorescence microscope then captures images of these glowing particles, and software counts and measures them. This method is fast and inexpensive, but it doesn’t actually identify what polymer a particle is made of; anything hydrophobic can light up, including fats, biofilm, or natural debris. Because of this, Nile Red isn’t really useful for microplastic quantification in biological samples.

[2]

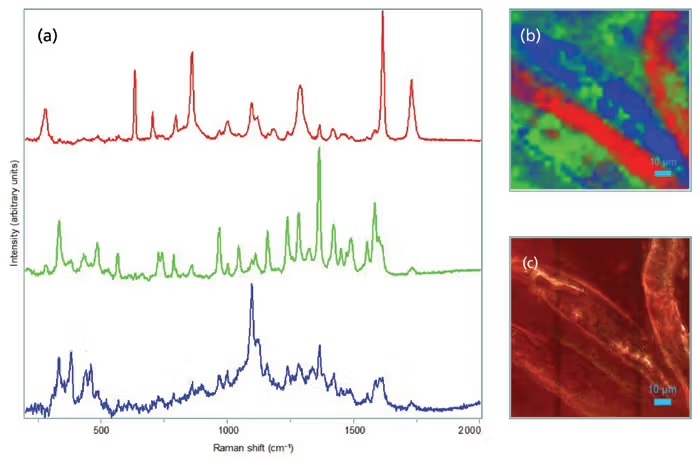

A more intense and sensitive technique is called µ-FTIR, or micro-Fourier Transform Infrared imaging. The way this works is by reading the unique infrared signature of a particle’s molecules to determine what it’s made of. This is accomplished by shining infrared light on a particle and measuring which wavelengths get absorbed. Every material’s molecules vibrate in characteristic ways when hit with IR light, so the pattern of absorbed wavelengths (the particle’s infrared spectrum) acts like a molecular fingerprint. The instrument’s microscope focuses the IR beam down to particles as small as ~10–20 microns, collects their spectra, and then software compares each spectrum to a library of known plastics. If the pattern matches, the particle is classified. The main drawback of this technique is that it’s expensive and time consuming; the equipment to perform FTIR spectroscopy usually starts at $150,000, and a full lab-ready setup can cost up to $300,000. The most intense/sensitive technique is called micro-Raman imaging. It works similarly to FTIR: shining a focused laser on a particle and measuring how a tiny fraction of the light scatters with shifted wavelengths. These shifts occur because the laser energy excites molecular vibrations, and the amount by which the scattered light is “shifted” is unique to each polymer’s chemical bonds. Compared with micro-FTIR, Raman uses visible/near-IR light and can be focused to much smaller spots, allowing detection of particles smaller than a micron. The microscope scans a particle or an entire sample, records the Raman spectrum for each pixel, and matches the spectrum to a library of known plastics. The main limitations are that some samples fluoresce strongly (masking the signal), that the equipment is quite expensive ($250k-$500k), and that mapping large areas is slow.

[1]

Image detection generally has some major advantages, in that (except the Nile Red technique) it’s non-destructive of the sample. Also, particle characterization (size, shape, composition, and location) can be very informative for understanding or hypothesizing biological interactions; non-visual methods don’t give particle-level data as they don’t tend to directly observe the shapes of the particles. Thermal methods generally are the most accurate way to get the mass (and therefore concentration) of plastic contamination in a sample, though the drawback is that this process destroys the sample through heating. One technique, pyrolysis-GC/MS measures the mass of different plastics in a sample by heating it rapidly until the polymers thermally break apart into smaller “marker” molecules that can be separated (by GC, or “gas chromatography”) and identified by mass spectrometry (MS). Each polymer breaks into a characteristic pattern of fragments, like a chemical barcode. By calibrating against standards, the instrument estimates how many micrograms of each polymer were present, regardless of particle size or shape. The gas chromatography + mass spectrometry setup that performs this process is extremely expensive, routinely costing over half a million dollars; this expense is compounded by expensive consumables (like the gas that runs the gas chromatography) Another is called TED-GC/MS, or thermal extraction desorption GC/MS, is similar to Py-GC/MS but uses more controlled heating and allows larger sample amounts. Instead of flash-pyrolyzing the whole sample, the material is gradually heated, causing different polymers to vaporize at their different critical temperatures. These vapors are swept into a GC/MS for separation and identification. TED-GC/MS is particularly good for complex sample types like soil and food because it can handle more material and gives cleaner separation of polymer types. As with pyrolysis, it provides polymer mass but not particle counts or sizes. It’s also quite expensive and takes a medium amount of time per sample (~90min).

[3]

Polymer composition is captured quite well by this method, however to fully analyze microplastics it can be important to get shape & size information on the particles themselves. Thus, thermal methods are often coupled with image detection techniques to fully characterize the microplastics in the matrix. Due to the increasing understanding of nanoplastics and their potential interactions with organisms, novel techniques are being assessed for quantifying nanoplastics and other particles. One of these is called FFF-MALS, or field flow fractionation + multi angle light scattering. It works by separating particles in a flowing liquid channel based on their size. A cross-flow pushes particles toward a membrane; smaller particles diffuse back into faster flow regions and therefore elute later, while larger ones stay closer to the wall and elute earlier, creating size-based separation without a physical filter. As particles exit the channel, a MALS detector measures how they scatter light at multiple angles to determine their radius and concentration. This gives a high-resolution size distribution down to tens of nanometers. However, FFF-MALS does not identify what polymer the particles are made of unless the collected fractions are analyzed with spectroscopy or mass spectrometry afterward. A different approach to understanding plastic contamination gaining some use

[4]

is to measure plastic-related additives in foods rather than quantifying the plastic particles themselves. Instead of counting microplastics, this 2024 study sent food samples to an accredited analytical chemistry lab, which screened for a suite of common plasticizers and monomers (such as phthalates, BPA-type compounds, and their modern substitutes) using standard GC/MS and LC-MS/MS methods. These chemicals often migrate from plastics into food, and their presence can indicate contact with plastic equipment, packaging, or contaminated ingredients. This additive-based approach is fast and scalable, and it works even when plastic particles are too small to detect directly. However, it cannot distinguish the amount, size, or type of any microplastic particles present, nor can it differentiate between contamination from packaging versus processing. As a result, additive quantification is best viewed as a complementary lens on plastic exposure rather than a substitute for particle-level microplastic measurement.Image detection methods

Thermal methods

Nanoplastic detection methods

Comparison of techniques

Technique

Cost

Throughput

Min Size

Polymer ID?

Nile Red

$

Very fast

~20–50 µm

No

Stereo microscopy

$–$$

Fast

~50–100 µm

No

Micro-FTIR

$$$

Slow

~10–20 µm

Yes

Micro-Raman

$$$$

Very slow

~1 µm

Yes

FFF-MALS (AF4-MALS)

$$$$

Medium–slow

~20–50 nm

No (unless coupled)

Py-GC/MS / TED-GC/MS

$$$$

Medium

N/A

Yes (polymer mass only)

Alternative approaches

References

- FTIR and Raman imaging for microplastics analysis: State of the art, challenges and prospects, Xu, et al., 2019.

- Quantification of Microplastics Mass Concentration using Images of Microplastics Stained with Nile Red, Park, et al., 2022.

- Micro and Nanoplastics Identification: Classic Methods and Innovative Detection Techniques, Mariano, et al., 2021.

- Data on Plastic Chemicals in Bay Area Foods, PlasticList, 2024.