Modern architectural paints fall into two broad families: water-based latex formulations and oil-based (alkyd) formulations. Although the pigments and fillers are mineral, the binders and most additives in contemporary paints are synthetic polymers. As a result, nearly all commercially available interior and exterior paints contain some plastic.

From a materials standpoint, the visible dry film of paint is a thin polymer composite that remains on walls for decades. It is not structural, but it is everywhere in modern buildings and contributes meaningfully to indoor dust composition. [1]

Natural, zero-plastic paints have been made and used for millennia, and can be readily made at home or purchased from specialty suppliers, though their adoption in the contemporary built environment is quite minimal.

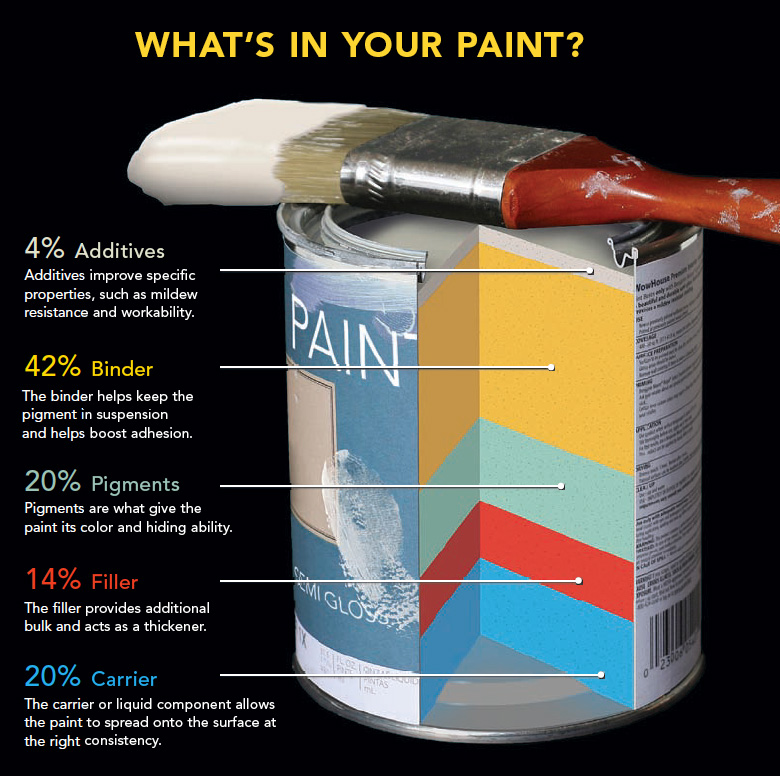

All paints contain the same broad categories of ingredients, differing mainly in the binder used.

Basic components of architectural paint Pigments give the paint its color and opacity. Generally, opacity is provided by mineral powders such as titanium dioxide, iron oxides, clay, and chalk. Organic chemicals like lake pigments and azo dyes provide brighter or more saturated colors. Pigments are zero-plastic. Many organic pigments are fugitive, which means their color degrades with exposure to the environment. Thus, they are used in lower proportion in architectural paints (which must ideally resist years of exposure to sunlight and the elements) compared to paints used in art or on indoor consumer goods. The binder is the substance that sticks the pigment to the surface it’s applied to. In modern paints this is almost always a synthetic polymer. Latex paint refers to water-borne acrylic or vinyl-acrylic emulsions: microscopic plastic particles suspended in water. Oil-based paints use alkyd resins as the binder. Specialty coatings like bathroom paints, kitchen enamel paints, porch paints, and floor coatings, use high-performance binders (often modified acrylics or urethanes) for moisture, abrasion, or chemical resistance.

[4]

Before the invention of plastics, paint binders mostly consisted of drying oils like linseed oil, animal proteins like egg whites, casein, and collagen, mineral binders like lime and potassium silicate, and various plant resins, gums, and waxes.

[5]

The “solvent” or “carrier” is the fluid that the paint ingredients are suspended in, to allow easy application to surfaces. Water is the main solvent in latex paints, though a coalescing agent like glycol is also often involved.

[2]

Oil-based paints rely on petroleum-derived solvents like mineral spirits that evaporate during curing, which is why they can smell stronger. Prior to the discovery of petroleum distillation, turpentine, alcohol, and other organic solvents were used instead of mineral spirits. In water-based paints, when the paint dries, the solvent evaporates and the binder particles fuse into a continuous film. In oil-based paints, the solvent evaporates but the binder particles don’t fuse right away–they instead oxidize, which causes them to polymerize due to their chemical makeup. The final coating is not very thick but is essentially a thin sheet of binder containing embedded mineral pigment. For the vast majority of modern paints used in construction and industry, that means this coating is a thin layer of plastic. Additives in small amounts, like plasticizers, dispersants, surfactants, and defoamers, can be included to improve flow, leveling, and stability, among many other qualities. Preservatives and mildew-killing substances are also standard in most indoor formulations. Generally, these constitute a small percentage of the total mass of the paint, most often less than 5% of the whole.

[6]

Many additives are inorganic compounds like silicates and metal oxides; plasticizers are generally petroleum derivatives like long-chain polyesters or liquid chlorinated paraffins. Dispersants in water-based paints are generally sodium- or potassium salts of water-soluble polymers. In oil-based paints dispersants can be a wide range of materials: calcium- or zinc sulfonate, aromatic ethoxylates (related to polycyclic musks), and soy lecithin, to name a few. These additives are usually included for ease of manufacture, regulatory compliance, and minor features like antimicrobial properties or ease of application. Thus, it is possible in principle to produce paints without them. That said, mass-market paints are rarely transparent about specific additive composition, and it may thus be difficult to find true zero-plastic paints on the market when additives are taken into account. Primer applied before finish coat Primers improve adhesion and provide a uniform base for finish coats. The majority of modern primers are water-based acrylic systems containing similar polymers to the topcoat. The main difference between primers and latex based paints is that primers have a higher solvent content, and less pigments.

[2]

Concrete and masonry primers typically include more robust acrylics designed to tolerate alkaline substrates.

[3]

Metal primers often rely on rust-inhibiting pigments like zinc phosphate held within polymer binders. Metal paint cans remain common, but many consumer products now come in plastic buckets or pails. Roller trays, roller frames, brushes with synthetic bristles, drop cloths, liners, and mixing sticks can incorporate plastics. Metal trays, canvas drop cloths, wood mixing sticks, and wood paintbrushes with natural bristles are widely available. Paint rollers not made from plastic are suprisingly not available; even those advertised as wool almost always have a synthetic inner core. Spray systems, whether air spray or airless, generally involve pressurized fluid flow. The requirements of pressurized application necessitate o-rings, mechanical seals, and the like, which are almost always made of synthetic elastomers. Mineral paints use inorganic binders like lime, potassium silicate, or clay, which harden through chemical reactions rather than polymerization: Linseed oil paint being applied to a woodworking piece Made from inexpensive materials, mineral paints were widely used for thousands of years on masonry, plaster, and stone. Casein paints use milk protein as a natural binder. When mixed with alkaline materials such as lime or borax, casein forms a hard, mineral-like film. Casein paints have been used historically on walls, wood, and furniture, and are still sold today for interior applications. Shellac is a resin secreted by the lac insect and harvested from tree branches. Dissolved in alcohol, it forms a brushable coating that dries rapidly as the solvent evaporates. Shellac has long been used on wood trim, cabinetry, and floors. Even after decades, degraded shellac coatings can often be restored by reintroducing alcohol, which partially re-dissolves and re-levels the film rather than requiring full removal. Traditional Asian lacquer (urushi) is derived from the sap of the lacquer tree and cures through enzymatic polymerization in humid conditions. It forms an exceptionally durable, chemical-resistant surface without petrochemical inputs. However, urushi is highly allergenic during application and requires specialized handling. In modern usage, the word “lacquer” often refers instead to synthetic products, such as acrylic or nitrocellulose lacquers, which are chemically and materially distinct from traditional natural lacquer. Linseed oil paints represent one of the few remaining paint systems that use a natural drying oil as the primary binder. Made from purified linseed oil and mineral pigments, these paints cure through oxidation rather than solvent evaporation or polymer coalescence. They are commonly used on exterior woodwork, windows, doors, and metal, particularly in historic and traditional construction. Unlike alkyd paints, these formulations contain no synthetic polymer binder, though they cure slowly and require thin application. Together, these natural and mineral-based systems illustrate that non-plastic coatings remain viable in contemporary construction, albeit with narrower substrate compatibility and different performance characteristics than modern polymer paints.Pigments

Binders

Solvents and carriers

Additives

Primers, sealers, and specialty coatings

Containers, tools, and accessory materials

Natural paints and alternatives

References

- Paints and microplastics: Exploring recent developments to minimise the use and release of microplastics in the Dutch paint value chain, Faber, et al., 2021.

- Generic Latex Paint Products, NIST, 2021.

- PERMALOK 100% Acrylic Masonry Primer Product Data Sheet, McCormick Paints, 2020.

- Paint Binders, roberlo.com, 2025.

- Binders and their tasks, romoe.com, 2023.

- 2011 Additives Handbook, Koleske et al. for Paints & Coatings Industry Magazine, 2011.